Filament Cloud Infrastructure

While working remotely at Filament, I built an end-to-end cloud infrastructure using AWS, Terraform, Node.js and Vue.js to help us test, validate and deploy our industrial-strength GPS tracking hardware.

Filament is a small startup based in Reno that provides secure device-to-device communication for the industrial internet of things. In 2017 we were focused on delivering edge hardware for industrial sensing, using secure wireless mesh networking to autonomously connect remote monitoring devices to each other and send sensor data to the cloud.

Needing a cloud of our own.

As we were preparing our industrial-strength GPS tracking device for the market, we had an exciting opportunity with a future client to pilot thousands (and potentially deploy millions) of devices out into the world.

Those were huge numbers for our scrappy team. To meet the client’s requirements we would need to be able to ramp up quickly, and ramp up big. In order to test, validate and deploy our remote sensing hardware, we would need an end-to-end cloud infrastructure where we could collect, store and visualize sensor data. Given the need to rapidly scale to handle thousands or even millions of devices, we chose to implement a cloud-native infrastructure that would be able to scale with us, leaving the drudgery of server administration to another party.

Volunteering as tribute.

Filament has a brilliant software engineering team with previous cloud infrastructure experience, but at the time they were all slammed with readying our device firmware for production. Our head of product, also an engineer, was busy with the industrial design of our tracking device enclosures, choosing materials that could withstand ten years of UV exposure, survive in a salt fog, and maintain RF-transparency even when covered in seagull poop.

As the senior design technologist at Filament I was familiar with code and servers, and I had tinkered on all the major cloud platforms. More importantly, I am curious and fearless. I starve if I’m not building things and learning new stuff every day. I had never built an entire infrastructure before, but I was pretty sure I could figure it out.

I raised my hand, and started eating documentation for breakfast.

Infrastructure Overview

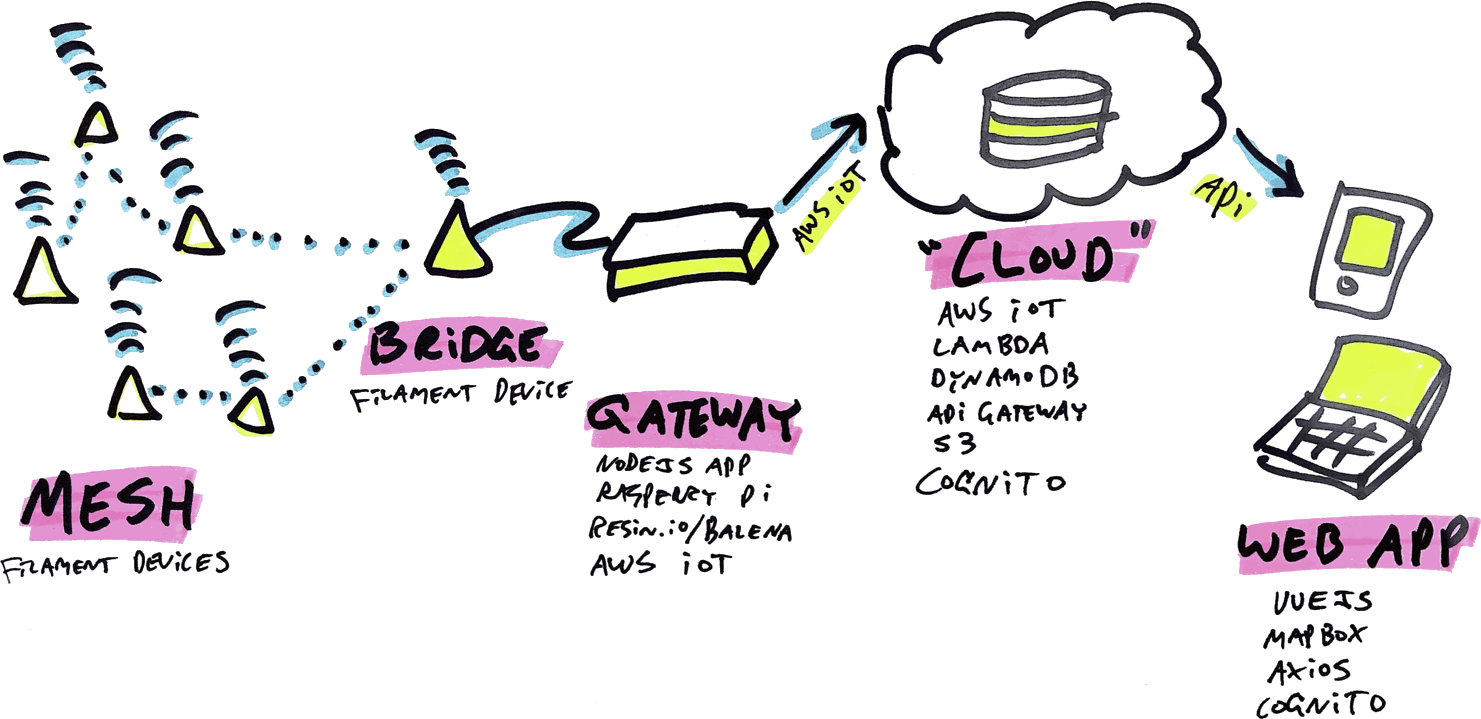

The infrastructure I built for Filament was hosted on AWS using Amazon’s cloud-native services, and consisted of four main pieces:

- A Node.js gateway app, running on a computer connected to a Filament bridge device, which receives sensor readings from all remote devices on a Filament mesh network, and securely sends that data to the cloud via AWS IoT.

- A cloud infrastructure, built using AWS services, which receives sensor data from any number of authorized gateways, parses and stores that data, and makes it available via a secured API to authorized agents.

- A static web app built in Vue.js, hosted on AWS S3 and secured via AWS Cognito, which retrieves sensor data from the API and displays all Filament devices on a map in real-time.

- An “infrastructure as code” configuration, written with Terraform, which allows us to quickly, consistently and repeatedly spin up our entire end-to-end cloud infrastructure with as little manual effort as possible.

If you enjoy code, I open-sourced much of the infrastructure and put it up on GitHub. If words are more your speed, please read on!

The Mesh

Using a protocol called telehash, Filament devices are able to self-organize and form an encrypted mesh network with each other without requiring predefined roles or routes. Filament builds the hardware and writes the device firmware that makes this magic happen.

The Bridge

Within a mesh, a single Filament device acts as the bridge, receiving all messages and sensor data from all the devices on the mesh. While all Filament devices can communicate with one another via the mesh, each device aims to get its data to the bridge through the best path possible, even if that path requires multiple “hops” through other devices.

The Gateway

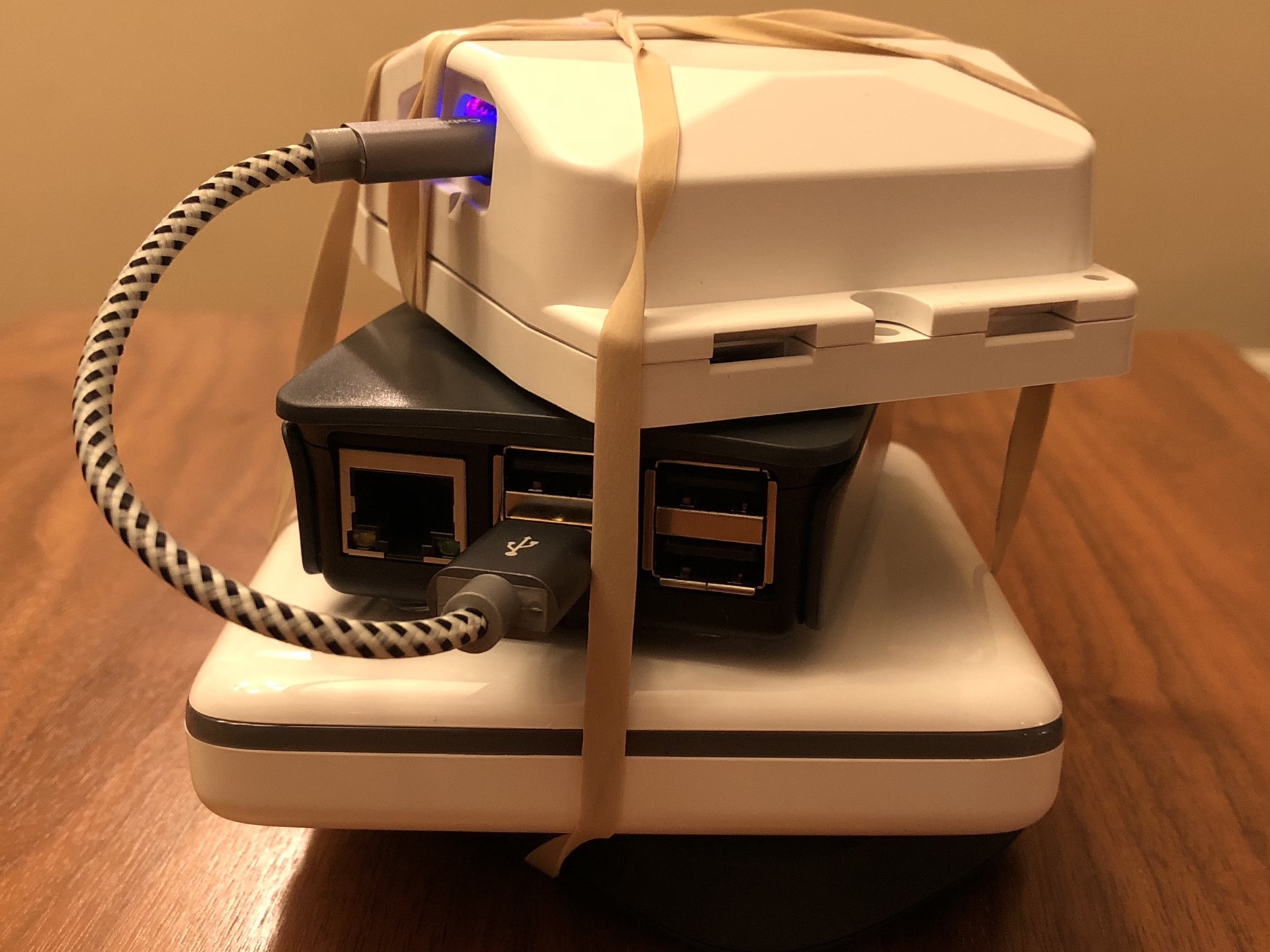

The Filament bridge device is connected to a gateway via USB, which it uses for both data transfer and power. The gateway hardware is simply some form of computer, and could be anything from a Raspberry Pi, to someone’s Mac or PC, to a tried-and-true industrial gateway device like the Advantech UTX-3115.

With our cloud infrastructure we assume that the gateway has internet connectivity, either through Ethernet, Wi-Fi, a cellular modem, or a MiFi hotspot. The Filament SDK and a corresponding gateway app are necessary for shepherding sensor data from a Filament bridge device to some form of storage via the gateway hardware.

Written in JavaScript, the SDK runs anywhere we can run Node.js, which means I’ve built gateway apps that run inside a native macOS/Windows app built with Electron, execute directly on a Raspberry Pi, or deploy to multiple hardware platforms via BalenaCloud (née Resin.io).

In the case of our cloud infrastructure, most Filament teams used Raspberry Pis as their gateway devices (there were exceptions… there are always exceptions!). Since Filament is a distributed company with team members in Reno, Tahoe, Minneapolis, Denver and San Francisco, I immediately needed a way to remotely deploy and manage the multitude of gateway devices and apps across our company sites. BalenaCloud proved essential for this purpose, and even allowed me to remotely support our sales team as they did onsite demos for customers across the country.

A gateway is only useful if it can send its incoming sensor data somewhere. While we used AWS for our cloud infrastructure, over the course of product development at Filament I built remote integrations for robust data solutions like Microsoft SQL Server and Losant, lightweight local integrations using SQLite, and the occasional raw integration using sockets or webhooks.

The “Cloud”

For our cloud infrastructure, I used AWS IoT to “bless” every authorized gateway device with a certificate so it could send up sensor data via a secure connection. When a device message arrives at AWS, a rule sends it along to an AWS Lambda function written in Node.js that parses and acts on it, adding a record to the events table at AWS DynamoDB, and adding/updating the device’s corresponding status in the devices table as necessary.

I used AWS API Gateway to expose an API that allows us to interface with the data stored in AWS DynamoDB, taking inspiration from the Slack API for the format and structure of our own endpoints. Each API request maps to a Lambda function that does the heavy-lifting of handling input, executing the query, and returning the results.

Access to the API itself is secured via AWS Cognito, so that only authorized agents, such as logged-in users, are allowed to execute requests against the API.

The Web App

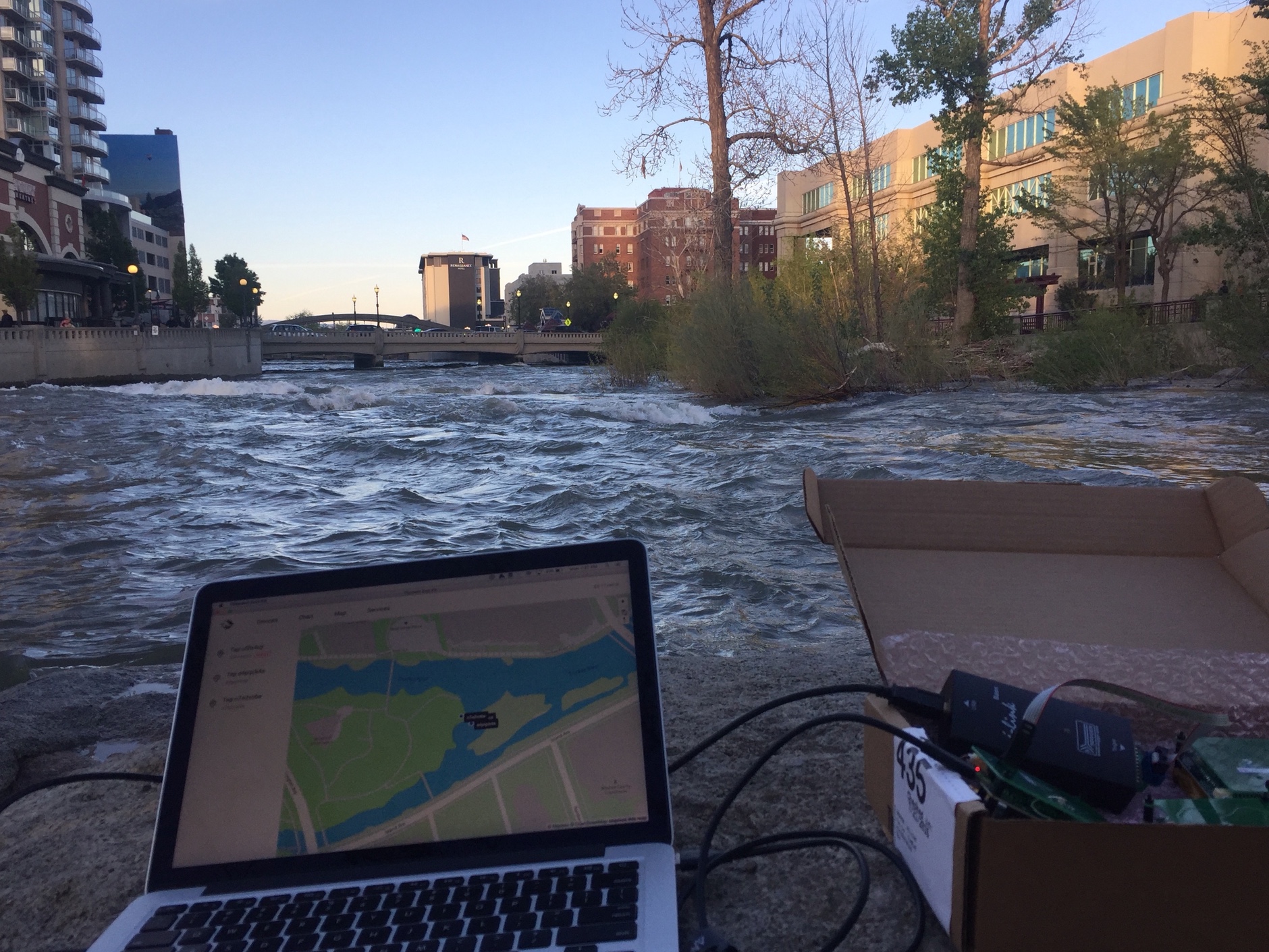

Filament’s key product at the time was a ruggedized GPS device for tracking unpowered industrial assets, such as valuable materials and equipment on a large construction site. Location and motion tracking were critical to our product, and the app I built for visualizing our collected sensor data was focused on mapping as well.

Using Vue.js and Mapbox, I built a mobile-first, responsive web app that plots the current or last-known location for all our devices on a map. The app renders down to static HTML, CSS and JavaScript for easy hosting on AWS S3 or any static hosting provider, and is secured with AWS Cognito so that only authorized users can log in and use it. All device data displayed in the web app comes directly from our API, using Axios to make authorized requests with the logged-in user’s Cognito token.

The cloud infrastructure proved indispensable for testing Filament device hardware and firmware. With all eyes on our incoming sensor data, visualized in real-time on a map, we were able to quickly uncover and squash bugs related to everything from GPS lock fidelity to parsing anomalies. Indeed, our QA team often hit the road with a Raspberry Pi, bridge device, MiFi hotspot, and a backpack full of tracking devices, and tracked their progress by firing up the web app on their phone.

Best of all, the map was cool, fun and just a little bit magical! Seeing all our devices across the country come together put a spring in our distributed team’s step, and it was exciting over the following weeks and months to watch more and more new devices come online. We “knew” our devices only by their eight-character hash names, but to this day I still have a soft spot in my heart for uxthswor, iglesggu, fxaq3wsf, and their respective personalities.

Infrastructure As Code

It was extremely important to me that the process of creating our cloud infrastructure be well-documented and repeatable. Mashing buttons in the AWS console until something works is a great way to learn, but it’s not a great way to build a reliable, maintainable, “knowable” system.

I used Terraform to define, script and automate as much of our infrastructure as possible. I couldn’t automate everything, of course, and automation itself follows the law of diminishing returns. Some newer AWS services like Cognito had incomplete Terraform Providers, and some Providers had bugs that required workarounds. Some of those workarounds required I dip in and execute AWS CloudFormation scripts from Terraform, and some of them had no script-able equivalent at all. I methodically documented everything, especially the things I couldn’t automate.

As a result of these efforts, it became trivial to spin up and maintain unique infrastructures in multiple environments for different purposes at Filament. We had a “development” environment, of course, which is where I worked day in and day out. I’d destroy and rebuild that environment multiple times a day, and anyone else who was trying to use it for anything was simply fooling themselves.

We also had a “testing” environment, which is where our product and QA teams would test device performance in different scenarios, validate updates to our device firmware, and provide feedback on the cloud infrastructure, gateway apps, and web apps themselves. This environment was reasonably stable, and I would only destroy and rebuild it after checking with everyone who relied on it.

Finally, we had a “production” environment. This was by far the most stable environment, and was used by everyone in the company for a little bit of everything, customer demos included. I rarely blew up this environment (on purpose, at least) and would only apply Terraform configuration changes in a controlled setting (for example, after beer but before whiskey).

Open source (most of) the things!

Sometimes, as in startups, as in life, it doesn’t quite work out. A couple months after I completed the initial implementation of our cloud infrastructure, Filament pivoted and we no longer needed it. As a company we took a deep breath, and as an individual I took the time to open source what I could from the infrastructure I had built.

All the hard parts of the cloud infrastructure, including the Terraform scripts themselves, are available on GitHub. What’s hard and what’s interesting aren’t necessarily the same thing, of course. Much of the interesting stuff was specific to Filament device hardware, including real-time sensor data, device status, mesh health, GPS tracking, and that totally awesome map we all knew and loved.

The GitHub repo has a lightweight gateway app that demonstrates an AWS IoT integration, as well as a lightweight Vue.js app that demonstrates logging in via Cognito and making API requests. Without our little devices and the inexplicable emotional attachment that comes from laboring over them, however, I don’t know how much the code on GitHub will mean to you.

It simply means a lot to me.

Project Responsibilities

Infrastructure Strategy, Architecture, Development, Testing, Documentation and Deployment

Project Technologies

Terraform, Node.js, BalenaCloud, AWS IoT, Lambda, DynamoDB, API Gateway, Cognito, S3, Vue.js, Mapbox

Project Team

Jake Ingman

Eliot Landrum

Dane Petersen

Project Timeline

May – August 2017